Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury has become a real puzzle for physiotherapists and physical trainers in high performance, but also in amateur sports. The incidence of injuries, that is, the number of ACL tears by practitioners, in pivotal sports such as soccer, handball, volleyball, etc. It is at 3% annually in amateur sports, which could rise to 15% in high performance, a percentage that has doubled in recent years. Women are the most affected by this injury (1).

BIOMECHANICS OF THE ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT

The ACL is a central ligament of the knee. The main functional role of the ACL is to provide stability against anterior tibial translation (TTA) and internal rotation. When the ACL is torn, the anterior tibial translation increases up to 10 to 15 mm. The ACL has its origin in the medial area of the lateral femoral condyle and inserts into the center of the eminence of the tibial plateau next to the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus. The structure of the ACL has been described as two functional bundles: the anteromedial (AM) and the posterolateral (PL) bundles. These two bundles have been associated with different functions in complex anteroposterior and rotational stabilization of the joint (2).

JOINT PRESSURE AND INCREASE IN ARTHROSIS

After an ACL rupture with a posterior displacement of the rotary axis and increased instability, an alteration of intra-articular cartilage pressure seems evident. Several biomechanical studies have found a decrease in total joint pressure after an ACL tear. As a possible consequence of decreased joint pressure, knee flexion movement after an ACL tear is also reduced. In the ACL-deficient knee, there is a shift of the axis of rotation toward the medial compartment with slightly greater freedom of movement. Tibiofemoral contact points during a single-leg squat at different flexion angles were determined in one study. They found that there was significant displacement of the contact points on the tibial surface after an ACL tear, most of them at flexion angles close to 15°. In the medial compartment, the contact points shifted to a more posterior and more lateral position toward the intercondylar eminence. In the lateral compartment, a lateralization of the contact points was also observed, but without alteration in the anteroposterior axis. While total patellofemoral joint pressure and medial patellofemoral compartment pressure decrease after an ACL tear, lateral patellofemoral joint pressure increased (3).

PREVENTION

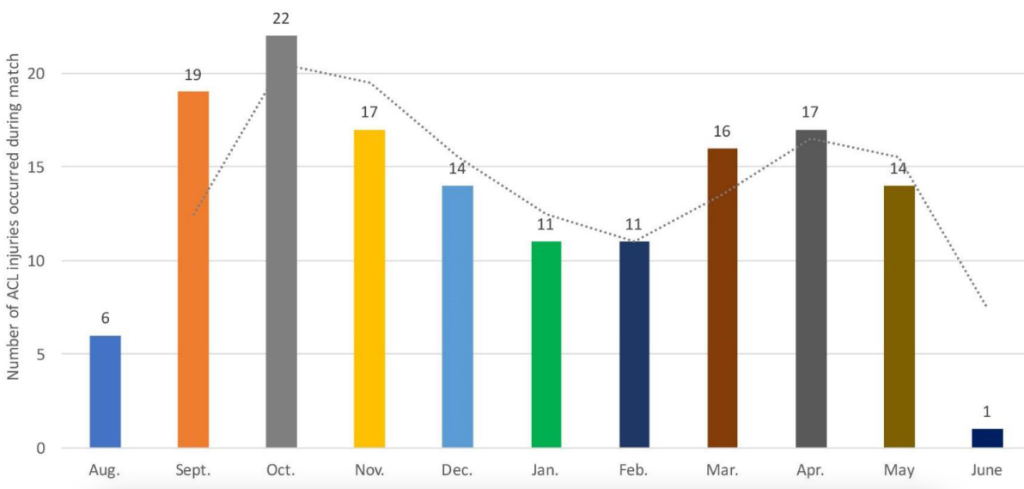

Prevention programs ARE NOT BEING EFFECTIVE CURRENTLY, the increase in physical demands in competition, together with the increase in competitive matches, are causing an increase in ACL injuries.

Prevention of ACL injuries, specifically in female athletes, has been well researched for more than three decades. Most of these neuromuscular training programs include a variety of strengthening, plyometric, and agility-based exercises that address deficits commonly associated with female athletes who have sustained an ACL injury. Several programs, such as 11+ (previously known as FIFA11+) were designed as a dynamic warm-up to increase implementation fidelity, adherence, and program compliance. But more recent evidence indicates that the mechanism of ACL injury prevention programs could consist of changing brain behavior using motor learning principles.

From a motor learning point of view, giving each athlete the opportunity to find their own motor solutions to movement problems may be more effective than instructing general team strengthening. Particularly the hip muscles, core and triceps surae, could be key for ACL prevention to be effective. It is logical that for athletes to change their movement pattern, there must be a change in their brain/neural activity, which is why the tasks must be individual. A neuromuscular program of the muscles mentioned above is associated with a decrease in the activity of the motor cortex, allowing an improvement in the transfer of practical patterns in complex environments, which allows an improvement in motor patterns and a decrease in injuries (4).

DETENTION

Stiff landings (large vertical ground reaction force, shallow hip and knee flexion) are associated with increased forces at the knee joint; however, purely sagittal plane forces are not likely to damage the ACL. But frontal and transverse plane biomechanics, such as medial knee shift or valgus collapse (hip adduction, hip internal rotation, and knee abduction), may be associated with ACL injuries.

Of the injuries, 88% occurred without direct contact with the knee last year. However, 44% of these ACL injuries occurred without any contact, which means that 56% of the injuries actually involved some form of contact elsewhere in the body (predominantly the upper part of the body or at the level of the pelvis). This mechanical disturbance, often combined with a distraction immediately before the injury, played an important role in causing these injuries in our cohort and has been shown to be important in other sports, such as basketball (5).

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

1. Arundale AJH, Silvers‐Granelli HJ, Myklebust G. ACL injury prevention: Where have we come from and where are we going? J Orthop Res 2022;40(1):43-54. Disponible en: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jor.25058

2. Melick N van, Cingel REH van, Brooijmans F, Neeter C, Tienen T van, Hullegie W, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med 2016;50(24):1506-15. Disponible en: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/24/1506

3. Domnick C, Raschke MJ, Herbort M. Biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament: Physiology, rupture and reconstruction techniques. World J Orthop 2016;7(2):82-93. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4757662/

4. Grooms DR, Kiefer AW, Riley MA, Ellis JD, Thomas S, Kitchen K, et al. Brain-Behavior Mechanisms for the Transfer of Neuromuscular Training Adaptions to Simulated Sport: Initial Findings From the Train the Brain Project. J Sport Rehabil. 2018;27(5):1-5.

5. Della Villa F, Buckthorpe M, Grassi A, Nabiuzzi A, Tosarelli F, Zaffagnini S, et al. Systematic video analysis of ACL injuries in professional male football (soccer): injury mechanisms, situational patterns and biomechanics study on 134 consecutive cases. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(23):1423-32.